VLM + RL + Data (Environment) = GUI Agent

Since GPT-3, teaching AI to operate computers and phones has been a persistent ambition. Many systems have been proposed—some tool-centric, some rule-driven, some fully end-to-end. Given the breadth of prior work, in this post, I focus on one route that is increasingly convergent in the literature: use reinforcement learning (RL) to train a vision-language model (VLM) to act as a GUI agent end-to-end.

Vision-Language Model

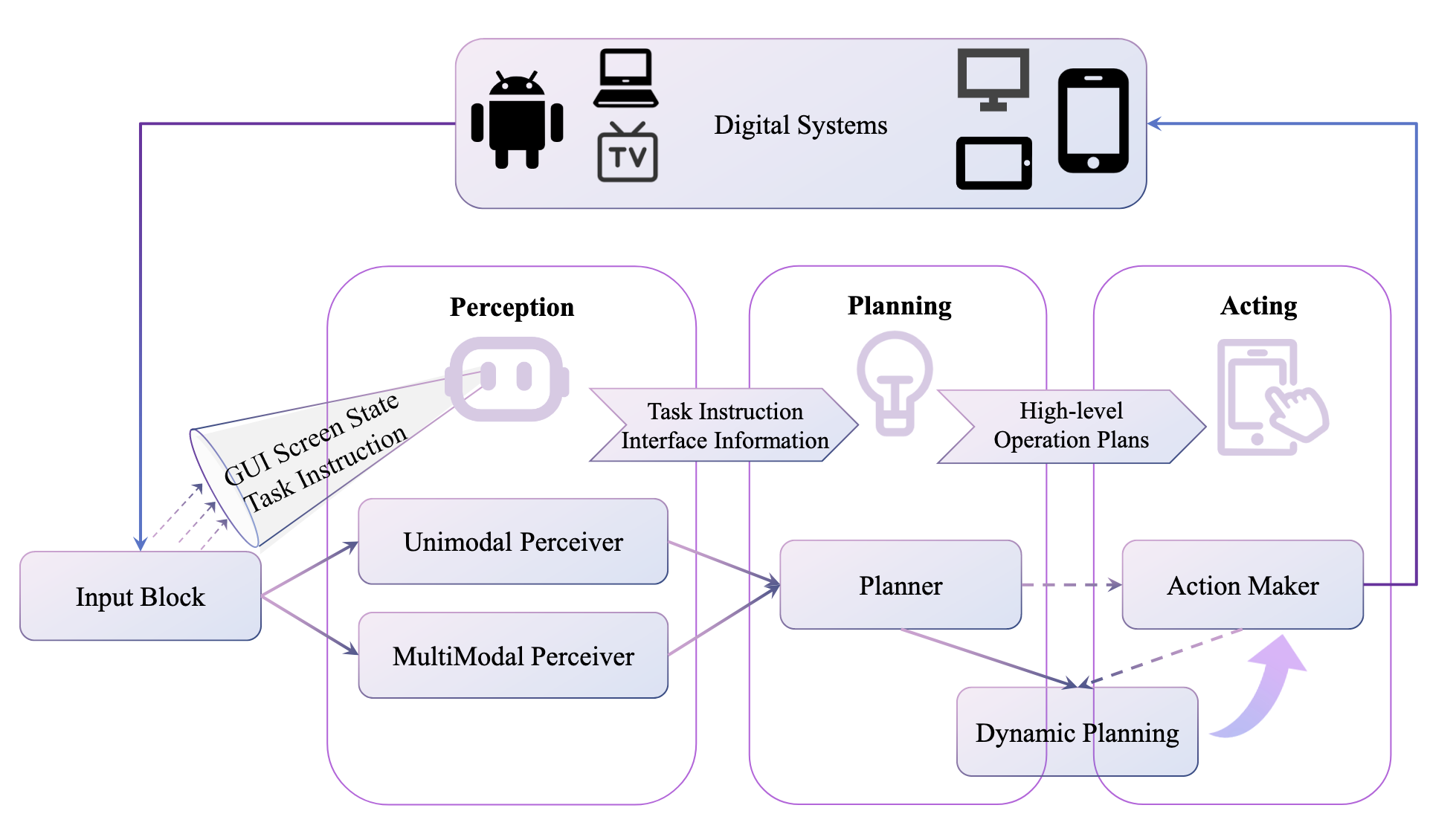

A straightforward way to automate GUI action is to use prompt engineering with a VLM and, in multi-stage designs, delegate planning to one model and grounding to another [1–2]. This decomposition can be useful in simple settings, but it relies on rigid interfaces between models: if the planner's outputs deviate even slightly from what the grounding model expects, the whole pipeline may break. Such fragility makes cross-domain transfer difficult and limits robustness under interface changes. For this reason, the field is now converging on unified architectures where a single vision-language model carries perception, reasoning, and action. In addition, hand-crafted pipelines tend to plateau quickly, whereas learned, end-to-end systems continue to improve with scale and interaction signal. Reading "The Bitter Lesson" provides useful historical intuition for why general, learned systems ultimately win out over manual decomposition [3].

General-purpose VLMs bring strong priors from vast pre-training corpora, but GUI control is a distinct domain. Screens are high-resolution and densely populated with small, function-bearing elements; models often miss tiny icons without special treatment [4–5]. Semantics depend on hierarchical layout and affordances rather than natural-image statistics, and robust localization remains hard under resolution constraints [6–7]. GUI interfaces also evolve at runtime: pop-ups, notifications, and layout drift introduce non-stationarity and noise that perception must handle gracefully [8–10]. Finally, tasks unfold over long horizons with stateful dependencies across applications; scalable, reliable long-horizon reasoning remains open [10].

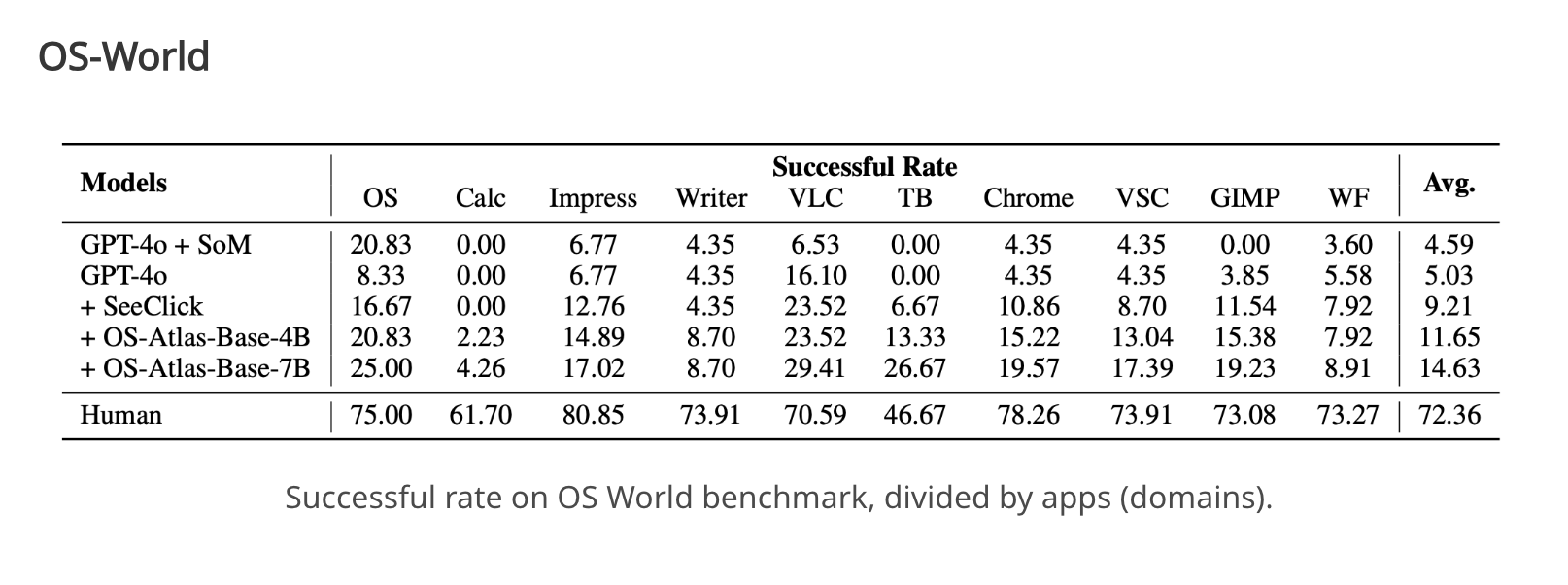

In response to these domain-specific challenges, the community has built GUI-centric perception datasets and models and then used supervised fine-tuning (SFT) to specialize VLMs for precise grounding and action mapping. High-resolution and small-box localization are explicitly targeted by Aguvis and ScreenSpot-style resources [4], [12], while structural understanding of layout and affordances is stressed by WebSRC [6]. At the same time, OS-ATLAS curates a cross-platform atlas of OS-level elements and tasks and releases baseline models trained via SFT to improve grounded understanding across desktop domains [7]. Concretely, the OS-ATLAS project reports consistent gains of its SFT models on the cross-app evaluations and supplies reproducible training and evaluation recipes, illustrating the typical "pretrain for perception → SFT for domain specialization" pipeline.

However, the table above makes the limitation of SFT clear: even with domain-specialized pretraining and supervised fine-tuning, models remain far from human reliability on multi-application desktop workflows. With the rise of verifiable-reward RL—training regimes that compute rule-based task signals from the environment—RL is increasingly applied to GUI agents to optimize behavior over trajectories rather than single steps [11].

Reinforcement Learning

RL has a long history in sequential decision-making. When training a GUI agent, the interaction process between the agent and its environment is naturally formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), denoted as M = {S, A, T, r, γ}. In this formulation, the state space S corresponds to possible screen observations and instructions; the action space A includes clicks, text entry, scrolling, or higher-level API calls; the transition function T models how the interface evolves; and the reward function r provides scalar feedback. The objective is to learn a policy π(a∣s) that maximizes expected return. This framing makes reinforcement learning a natural fit: unlike supervised fine-tuning, which depends on annotated trajectories, RL can directly optimize behavior through interaction, particularly in long-horizon, multi-application workflows [12–13].

Verifiable reward. To use RL for training a GUI agent, we adopt a minimal, verifiable signal at each step. The state is the pair of instruction and screenshot; the action is the model's next-token output decoded as a click point . Given a ground-truth bounding box for the target element, the reward pays if the predicted point lands inside and otherwise—keeping the objective tightly aligned with correct interaction while remaining trivial to compute at scale [19].

Reward shaping. The binary indicator is only a starting point. We can shape rewards to stabilize learning and capture task geometry—for example a Gaussian reward around the box centroid (higher credit as the click approaches the center), format rewards that grant credit when model-generated output matches required patterns, and penalties for invalid or off-screen actions.

The benefits of RL in this setting are straightforward. GUI tasks incur compounding error and delayed credit assignment; RL directly optimizes long-term return rather than step-wise imitation. Rule-based or "verifiable" rewards allow programmatic checks of progress and completion, reducing the risk of reward hacking [13]. Empirically, these ingredients translate into better adaptivity under layout drift, more reliable error recovery, and improved cross-application transfer relative to SFT-only baselines.

People have already begun to apply RL to GUI agents, and the initial results are encouraging. For instance, the UI-TARS2 integrates multimodal perception with reinforcement signals to improve robustness under UI drift and long-horizon tasks, demonstrating clear gains over supervised approaches across domains [13], [14]. Similarly, benchmarks such as OSWorld show that RL-trained models can generalize better than SFT alone, achieving higher success rates on multi-step workflows across applications [10]. These results suggest that interaction-driven optimization is beginning to narrow the gap toward human-like reliability.

At the same time, the main obstacles exposed by these RL studies point beyond the optimizer. High-quality, up-to-date trajectories and learning-grade environments are scarce; many public corpora exhibit noise, outdated UI states, or narrow coverage [12], [13]. Environment ecosystems typically fall into three families—static replicas (e.g., screenshot snapshots), simulated or self-hosted websites (e.g., MiniWoB, WebArena/VisualWebArena), and real-world execution platforms (e.g., OSWorld, AndroidWorld/MobileAgentBench)—each trading off fidelity, controllability, and cost [8–10], [12], [15–17]. However, none of them yet meet the bar for scalable, verifiable, and economical data generation at once—each compromises fidelity, controllability, or cost. In short, as RL moves from proofs-of-concept to realistic settings, data and environments—not just algorithms—will increasingly determine progress.

Data for Reinforcement Learning

When applying RL to GUI agents, it is tempting to keep tuning the optimizer or add intricate reward shaping. But after taking a careful look at failure cases, it shows that many errors stem from signal quality rather than the policy update itself: incorrect bounding boxes that misalign clicks and targets, one-to-many instructions where a natural-language command can correspond to multiple valid UI elements but the dataset only marks one. In other words, the algorithm may be "good enough" on clean loops; what holds back reliability is the quality and timeliness of the interaction data.

Beyond environments, however, there is still no generally accepted, scalable method to acquire large-scale, high-quality trajectory data for RL. Existing collection pipelines either introduce too much noise (e.g., weakly verified outcomes, model generated ambiguous instruction, incorrect bounding box) or fail to scale economically to the volumes needed for robust long-horizon learning. In practice, this means policies trained with interaction remain constrained not only by algorithmic choices but by the lack of reliable, progress-aware trajectories at scale.

From a data perspective, the most promising path is to engineer environments as data generators, not because environments are the only solution, but because they can operationalize what high-quality trajectories require. If an environment can (i) verify terminal and intermediate conditions programmatically (reducing label noise), (ii) control drift and perturbations to expose robustness gaps systematically, and (iii) scale via parallel, replayable execution, then it becomes a practical instrument for producing large volumes of reliable, progress-aware interaction data—precisely the bottleneck identified above. This does not preclude complementary routes (e.g., policy-guided logging with consent, rule-based reward extraction, or offline value modeling). The unifying principle is: Data quality is not merely a matter of collecting samples, but a system-level property—realized through systematic data curation or well-designed environments.

References

- OmniParser. "Structured UI Representations from Screenshots for GUI Grounding." 2024. GitHub

- SeeClick. "SeeClick: Harnessing General-Purpose Models for Click-Through GUI Grounding." Findings of ACL, 2024. Paper

- Sutton, R. S. "The Bitter Lesson." 2019. PDF

- ScreenSpot-Pro. "GUI Grounding for Professional High-Resolution Computer Use." 2025. arXiv

- CogAgent. "CogAgent: A Visual–Language Model for GUI Perception and Small-Element Localization." 2024. arXiv

- WebSRC. "Web-based Structural Reading Comprehension." EMNLP, 2021. arXiv

- OS-ATLAS. "A Cross-Platform Operating-System GUI Atlas for Grounded Understanding." 2024. Project

- WebArena. "A Realistic Web Environment for Building Autonomous Agents." 2023. arXiv

- VisualWebArena. "Evaluating Multimodal Agents on Realistic Visual Web Tasks." 2024. arXiv

- OSWorld. "Benchmarking Multimodal Agents for Open-Ended Tasks in Real Computer Environments." NeurIPS 2024. arXiv

- DeepSeek-R1. "Incentivizing Reasoning via Verifiable Rewards." 2025. arXiv

- Survey. "A Survey on (M)LLM-Based GUI Agents." 2025. arXiv

- Survey. "A Survey on GUI Agents with Foundation Models Enhanced by Reinforcement Learning." 2025. arXiv

- UI-TARS / UI-TARS2. "Unified Perception-to-Action Mobile/Android Agents with Reinforcement Optimization." 2024–2025. arXiv

- MiniWoB / MiniWoB++. "World of Bits: An Open-Domain Platform for Web-Based Agents." ICML, 2017. arXiv

- AndroidWorld. "A Dynamic Real-Device Benchmarking Environment for Autonomous Agents." 2024. arXiv

- MobileAgentBench. "A Benchmark for Mobile LLM Agents on Real Devices." 2024. arXiv

- Aguvis. "Aguvis: Unified Pure Vision Agents for Autonomous GUI Interaction." 2024. arXiv

- UI-R1. "Enhancing Action Prediction of GUI Agents by Reinforcement Learning." 2025. arXiv